Last Thoughts on Gerry Gable and his War Against the Fascists

Gerry Gable, the most tenacious post-war anti-fascist Britain ever produced, had been ill for some time when he finally passed away on Saturday, January 3, 2026. He was 88.

For half a century (and more), Gerry was the pulse of Searchlight. He was one of its founders, its publisher, its frequent editor, and the one constant while everyone else came and went (and sometimes returned). In the world of British anti-fascism, the man and the magazine were indistinguishable. Gerry Gable was Searchlight.

In February 2025, after 50 years and almost 500 issues, the final print run rolled off the presses as the magazine was launched as a fully online publication with Gerry’s blessing. Gerry was ill by then; it was the end of an era, but as he knew better than anyone, it was just the next phase in taking on the enemy. All the old editors and other friends that were still around pitched in.

“We’ve come to fix the phone line”

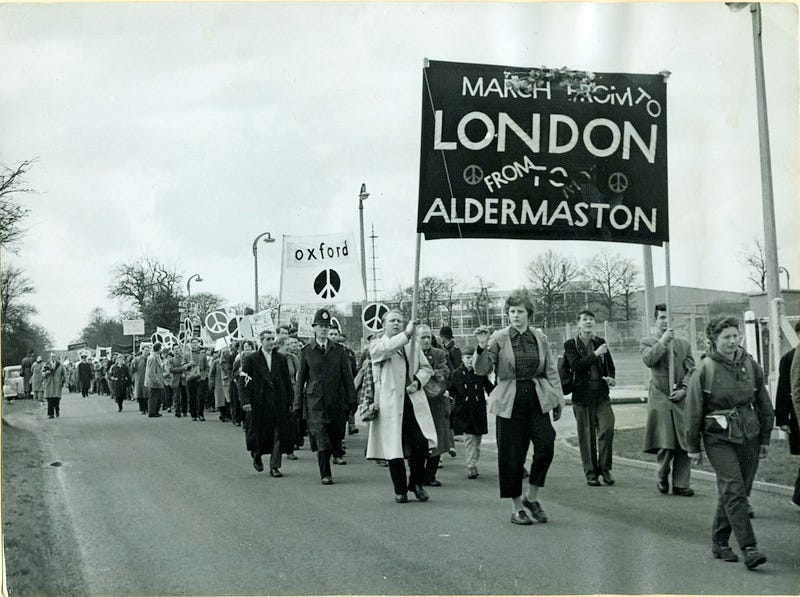

Long before he was an editor, Gerry was a man of action. He had been active in taking on the fascists during the period of the Notting Hill (Notting Dale) Riots in 1958 and defending CND’s early Aldermaston marches. He was a leading figure in the North East London Anti-Fascist Committee. His commitment to the “tradecraft of intelligence” was forged in the early 60s. Most famously, in 1963, Gerry and fellow 62 Group activist Manny Carpel posed as GPO engineers to gain entry to the flat of the Holocaust denier David Irving.

They were after Irving’s private papers to expose his fascist connections. Gerry ended up in court, but he never regretted it. For him, the law was a secondary concern when compared to defending the Jewish community and the exposure of the enemy. He knew Irving was a “wrong ‘un” when most believed at that point that he was a genuine historian, and he set out to prove it. It was this uncompromising, “by any means necessary” spirit that he carried into the founding of Searchlight the following year.

This action lined him up for expulsion from the Communist Party, of which he had been a full-time industrial organiser. They tried to imply that his activities were common criminality, but he pre-empted things and left telling one of their very well-spoken intellectuals who was in charge of the case:

“I don’t want to be in an effing party with people like you anyway.”

In later years, Gerry sometimes said that he left over the Party’s increasingly strong anti-Israel stance. It is likely that both things are true. Even though he left the Party, he carried its legendary education and methods with him for the rest of his life, regardless of the politics.

The Apprenticeship

I met Gerry when I was a teenage activist. He took me under his wing, but being mentored by Gerry wasn’t some cosy academic exercise. It was an education in the “tradecraft” — as he put it — of anti-fascist intelligence gathering.

He taught me that the street fight was only half the battle. Coming out of the 62 Group, Gerry wasn’t afraid of physical confrontation, but he knew the real damage was done through the use of information. He taught me how to trace the owners of post office boxes, raid bins, get addresses from phone numbers, build files on the enemy, and numerous other investigative skills.

But it wasn’t all tradecraft and dossiers. Gerry helped give me a political and cultural education, too. He introduced me to the classics of socialist and anti-fascist literature, from Jack London and Robert Tressell to Stetson Kennedy and Leopold Trepper. Through him, I discovered Woody Guthrie and the songs that gave a voice to the dispossessed. As a treat, when Bob Dylan toured Britain, Gerry would buy a bunch of tickets and take Searchlight staff and volunteers along. He understood that to sustain a lifelong struggle, you needed more than just facts; you needed a culture to anchor you.

My own experience is just one of many. Lots of one-time young Jewish activists are indebted to Gerry — and international editor Graeme Atkinson — for providing an anti-fascist home in a hostile political environment in their student days. Many of those who now hold senior positions in communal organisations or have carried out important work in TV, print, or other areas can recall hearing Searchlight mole Ray Hill speak at their university.

Link to the Past

Gerry maintained a link to the original pre-war and immediate post-war anti-fascists. I stayed at Gerry’s house numerous times, and we would often go visit Spanish Civil War veterans or a 43 Group member that he was in contact with. There were plenty of 62 Group activists still around and involved with Searchlight on a day-to-day basis in the 1980s, and these old comrades acted as if their organisation still existed as they pondered what seemed like hare-brained schemes to a young observer.

The esteem that he was held in by the older generation was driven home to me when I was involved with Anti Fascist Action (AFA). The organisation had a music arm called Cable Street Beat, and in 1988 we held a big concert at the Electric Ballroom in Camden with punk bands topping the bill. I was a member of the Communist Party and a frequent visitor to the party’s St John Street offices in Farringdon, where I knew Battle of Cable Street veteran and former long-standing Communist councillor Solly Kaye volunteered. I was tasked with approaching him to see if he would speak at the event. He had the usual suspicion a Communist veteran had that AFA might be an “ultra-left” outfit. He asked me directly if I was in touch with Gerry Gable. Gerry’s name was the only credential that mattered. The next time I saw Solly was at the Electric Ballroom.

Seeking Justice: The Soviet Union and the War Crimes Campaign

His fight was never just about modern thugs; it was about the unfinished business of the Holocaust. Throughout the 80s, he led a relentless campaign to bring Nazi war criminals living in the UK to justice. He was in touch with the legendary Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal and others internationally engaged in hunting down the perpetrators.

This wasn’t just desk work. At the height of the Cold War, Gerry headed into the Soviet Union to gather evidence. He didn’t go alone. Sonia, his wife, was there with him, as always. They travelled through the Eastern Bloc, gaining access to archives and massacre sites that the British establishment would have preferred be left alone.

They brought the evidence home and passed it to the All-Party Parliamentary War Crimes Group. For part of that time, I was the anti-racism officer for the Union of Jewish Students (UJS), and we worked hand-in-glove with Gerry. We mobilised the students while he provided the hard intelligence that forced the government’s hand against significant opposition from those in the establishment that thought we should leave these “old men” alone. That campaign was the engine behind the War Crimes Act 1991.

Entering the Den: Kensington Library, 1991

Gerry’s anti-fascism wasn’t a theory; it was a physical presence. I vividly remember the chaotic day in 1991 we entered Kensington Library in central London. Inside, the League of Saint George — an umbrella Nazi outfit — planned to hold a meeting.

I was with him when he addressed the victorious anti-fascists after the meeting never materialised, and the inevitable long legal fallout that followed. Gerry didn’t care about the police attention or the court dates as long as we did some damage to the enemy. Which we did.

The Tradecraft of Running a “Mole”

Gerry was a master at running “moles” inside the heart of the enemy’s camp. Sometimes they were fascists who had a change of heart and sometimes they were anti-fascists planted inside the enemy camp.

He knew how to manage the psychological pressure of those living double lives inside the National Front or the BNP. It was dangerous work. There were furtive meetings, calls from phone boxes, and the constant, gnawing threat of exposure. Things didn’t always go right, it could be an unpleasant business. But Gerry tried to look after people and all involved knew the risk. He did it because he knew that one well-placed asset could do more damage than a hundred protest marches.

The Price of the Truth

You don’t do what Gerry did without paying a price. The Searchlight offices were discovered by the fascists and threats made on several occasions. More frighteningly, his home was targeted.

When it first happened and he was going away on holiday, Searchlight team members took it in turns to stay at his house so it wouldn’t be broken into while he was away. We were all given worrying instructions on how to use the shotgun propped up at the top of the stairs:

“Aim low, you don’t want to end up on a murder charge.”

This wasn’t adventurism — it was a war of attrition. He lived a life of high security, checking under his car for bombs and suspicious of any unusual activity.

The Courtroom as a Battlefield

Gerry fought many legal cases with the fascists. We were involved in one significant one together: Roberts v Gable, Silver and Searchlight Magazine Ltd (2007). We’d run a piece on the internal civil war within the BNP, and two of their members decided to sue us for libel.

It was an attempt to bankrupt the magazine and silence Gerry as author and me as the then editor. We fought them on “neutral reportage” — the right to report on the internal wranglings of extremist groups without being held liable for the lies they tell each other. We won in the Court of Appeal. It was a victory for investigative journalists across the country, and a massive “no” to those who thought they could use the High Court to shut us down.

A Man of Conviction

Gerry could be a difficult man. In a number of areas of the work, it was his way or no way. This caused tensions if you worked with him and inevitably was one of the reasons that I left Searchlight, and then later the split with Hope not Hate came about.

Nevertheless, he didn’t hold grudges forever. After going our separate ways, friendly relations resumed. Gerry once paid a visit to Bob Crow, then General Secretary of the RMT trade union — no doubt to secure some funding. By then I was working for the union and went down to say hello. After decades of what was once daily contact, we hadn’t spoken much for a while. Gerry greeted me warmly and before we parted said: “Don’t be a stranger, Steve.”

At the end of the day, Gerry being difficult had a context. His “difficulty” was his armour — a necessary survival mechanism in a world where the enemy wanted him dead and rival anti-fascists found Searchlight a thorn in their side.

Conversely, Gerry was completely non-partisan and was as happy to work with a Tory or pass information to the police on fascist criminality as he was to work with a Trotskyist or Anarchist from a local anti-fascist group. He didn’t care what someone professed to believe but judged them on their (anti-fascist) actions alone. Sectarians — and there were plenty of them — found this approach difficult to reconcile and attacked him for it.

The Necessary Man

Gerry was capable of putting fascist groups in a state of paranoid frenzy and he revelled in it. He was their number one hate figure, regularly attacked in their publications. Sometimes, if we had a big success, he would phone them up and taunt them.

He was a man of the print era — nothing beat the smell of a glossy cover and a stack of magazines — but he had the foresight to see the battle moving online. He saw the launch of the new Searchlight website before he passed, knowing that while the medium changes, the methodology — hard intelligence over empty rhetoric — must remain.

Gerry Gable didn’t just witness the history of post-war British anti-fascism; he wrote it, edited it, and defended it. Britain is a significantly less hospitable place for fascists today because Gerry spent sixty years infiltrating, attacking and undermining them.

There is a famous quote by Bertolt Brecht that, while written about revolutionaries, sums up Gerry’s anti-fascism better than any long-winded eulogy:

“There are those who struggle for a day and they are good. There are others who struggle for a year and they are better. There are those who struggle many years, and they are very good. But there are those who struggle all their lives: these are the indispensable ones.”

Gerry’s legacy lives on. Lotta Continua!

Note on the text: The concluding quote is from the poem In Praise of the Revolutionary (originally appearing in the play The Mother, 1932) by Bertolt Brecht.

Beautiful tribute Steve .