Yesterday’s Witness and documentary pioneer Stephen Peet

When Stephen Peet joined the BBC documentary department in 1967 he sent a memo to the BBC controller David Attenborough about an idea he had for an “inexpensive film series of ordinary people talking about their memories of historic events or periods.” That led to the first six episodes of Yesterday’s Witnesses and made Peet the founding father of television oral history.

One of the first of those six episodes was The Battle of Cable Street about the day on 4 October 1936 when anti-fascists routed Oswald Mosley and his Blackshirt thugs in the East End of London. Shot in 1969, and first aired in early 1970, it is an extraordinary piece of television which features interviews with both fascist leader Oswald Mosley and the most well-known East End anti-fascist of the period Phil Piratin (later to become a Communist MP for Mile End).

A hallmark of the series was that in addition to well-known people it took ordinary witnesses to events and had them speak directly to camera. Previously, this had been the privilege of newsreaders and presenters. In The Battle of Cable Street there are three men in a pub in a heated debate about what Mosley stood for. As two of them discuss the topic the third man says about Mosley in a cockney accent:

“Give him a proper answer, a murderer, like all fascists are murderers. That’s the right answer, a truthful answer.”

The Cable Street programme wasn’t the only one that helped put major working-class struggles on the map: there were also programmes on The Burston School Strike and The Jarrow Crusade. Others interviewed witnesses from The Great Blizzard of 1891, The Tithe War and anti-fascist International Brigade Veterans of the Spanish Civil War.

History from below

The series ran between 1969 and 1981 and helped popularise history from below in a period where history for most British people still stank of Empire and what they learnt in school was mostly about kings and queens. In total more than 80 programmes were made, with Peet at the helm as producer, and the collaboration of filmmakers such as Michael Rabiger, Ian Keill and Rex Bloomstein.

Peet’s success at the BBC is testament to his remarkable talent as it turned out all along sinister forces were trying to undermine his work. Many years later it was revealed that he had been secretly blacklisted by MI5 who attempted to stymie his career. His crime? His brother was a former Reuters’ correspondent and communist sympathiser who made his home in East Germany at the height of the Cold War. I recently wrote about John Peet here.

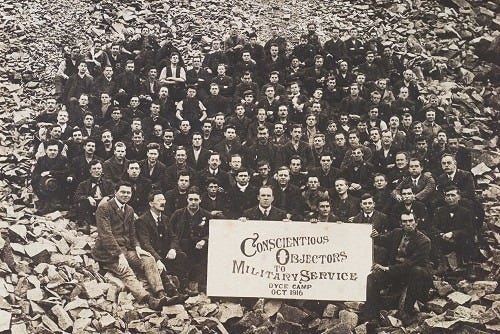

Stephen Peet was born in Penge South London to Quaker parents. His father Hubert was a journalist and editor of the Quaker magazine The Friend. Quakers of course are pacificists and Hubert Peet was a conscientious objector who served three terms of imprisonment for his refusal to obey military orders during the First World War.

It’s unsurprising then that Peet was motivated to make one of the Yesterday’s Witness programmes No to the Army, about the men who refused to fight in the First World War. No doubt his own experience as a prisoner of war in Nazi Germany was also a factor.

When the war started in the summer of 1914 every soldier in the British Army was a professional, a volunteer. By 1916 tens of thousands of them were dead, their lives squandered by the madness of their commanders on the battlefield. The answer to this crisis was conscription of men regardless of whether they wanted to fight. By May 1916 all able-bodied men between 18 and 41 were obliged, by law, to join the army.

Some 16,000 men: Quakers, socialists and others who for reasons of conscience refused to fight. They were publicly vilified in an atmosphere of extreme jingoism. Ultimately, their dignified struggle changed the way people who refused to fight on moral grounds were seen subsequently.

One of the programme’s interviewees was Fenner Brockway who became a Labour MP and by the time the programme was made was in the House of Lords. He said of their struggle:

“Undoubtedly in the Second World War conscientious objectors were treated more generously. It not only had an effect on the liberty for conscience in this country, but I think all over the world.”

Two kinds of life

A particularly interesting episode was called Two Kinds of Life which contrasted the lives of English debutantes during the Second World War with that of a young woman living under the jackboot of Nazism in occupied Europe.

Gergana Taneva was the teenage daughter of political refugees from Bulgaria who had both died by the time she was 16. She was one of tens of thousands of non-Jews who were incarcerated for political activities. It is said that she was the only person to have escaped from Munich jail. Without papers and on the run she was later caught and sent to the women’s concentration camp of Ravensbruck where she was lucky to survive the war.

Taneva described the awful conditions inside the notorious camp and how she survived along with other women who were detailed as slave labourers to work outside Ravensbruck:

“Then I got a job in Siemens factory. The famous firm of Siemens specially built a factory near the camp. They were earning quite a nice profit from the slave labour. So prisoners were driven every day through this tiny town of Furstenburg.

“Everybody knew about it. Everybody saw women without hair; women with striped clothes; women dragging bodies of their dead comrades who died during the work, or bitten to death by SS dogs… The people from this little town saw it all. And everybody knew about these concentration camps.”

The programme mentioned that after the war Gergana (or Georgia Tanewa as she was known) married an Englishman. One thing it doesn’t say is that the Englishman was Peet’s brother John and therefore Gergana was Peet’s sister-in-law. Interestingly, when the programme was made about the International Brigade veterans of the Spanish Civil War he didn’t interview John, who was a veteran.

After retiring from television in the early 1980s Peet lectured on documentary film-making and oral history across the world. When he passed away in 2005 at the age of 85 many documentary makers acknowledged the debt they owed to this pioneer of the genre.

There are some clips of the Yesterday’s Witness programmes scattered across the internet. You can view the entire Battle Cable of Street programme here.